Let Daigans Be Daigans

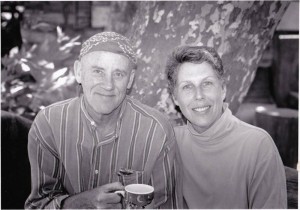

Daigan and his partner Arlene at Tassajara, summer 1995

Daigan and his partner Arlene at Tassajara, summer 1995

In May of 1995, I was perched nervously on a chair at the yurt in Tassajara, a Zen Buddhist monastery deep in the mid-coast California mountains, waiting for an evening talk to begin, trying to draw keep my spine straight and look stern yet serene, as I imagined real Zen students to be. A newly arrived resident at Zen Center and at Tassajara, one question was uppermost in my mind: Am I doing it right? Of course, other questions were waiting in the hold as well, questions that had led me to leave my home and reside in this deep canyon with a bunch of people whom I barely knew. Yet the necessity of adjusting to a place where social rituals are new and attention to form was quickly noticed and corrected had me in a tizzy of embarrassment and discomfort.

Most of the residents were already seated in a semicircle around an older man who immediately fulfilled my expectations of how a Zen priest should appear: tall, lean, with a lantern jaw and a spareness of aspect that stemmed not just from the black robe but also some inner determination. Hunched over a chair that seemed too small for him, he was smiling a half smile with eyes lowered as if at some private joke. Small clumps of people kept arriving in the yurt, mostly guests and guest students ambling over after a gourmet meal in the dining hall and probably not eyeing their watches so hard. More than once this priest–Daigan, I learned his name was, born as David Lueck–looked around and brought himself up as if about to start the evening, but then more people would arrive in little ragged waves, and more chairs were brought out, with a lot of concomitant scraping, shuffling and sniffing. I got nervous for those people. Surely they could arrive sooner and move about quieter. Surely this shaven-headed monk would tell them so. Instead the half-smile on his face eased into a full one, and the light that glowed like a film underneath his skin became stronger.

“Things are going to be like this all evening,” was his only comment. His voice was the opposite of his spare appearance–velvety, relaxed, and brimming with amusement. There were a few appreciative laughs, a bit more shuffling of chairs. And then he put his palms together and the talk began.

I would have the good fortune to meet other awakened teachers during the ten years I lived at Zen Center, but Daigan was my first. This small yet telling moment of grace, registered at the first dharma talk I attended as a resident, sunk deep into the mud of my mind and stayed there. Here was someone who had totally arrived and thus was ready to receive others when they did, no matter how punctual or unpunctual, silent or noisy, graceful or clumsy they were. He simply sat there and let us come, and then he talked to us, and he was intelligent and brave and utterly unpretentious, with an easy yet eloquent way of talking that I later learned came from his background in theater. Somehow, with this training, he had mastered the art of being self-effacing and dramatic at the same time. Or maybe he hadn’t mastered anything–maybe it was natural for him to be so.

He knew about and valued the precepts of posture, even while he shambled around, perhaps not used to having his tall silhouette accepted by low door frames. This was delightful, too—that he was so relaxed, so hanging in his joints. Joining a religious order was the last thing I figured I would do when I arrived at Zen Center; because of this, I had a tremendous sense of relief that someone like Daigan was around. If this artistic, solitary individual could do it, so could I. He was one of the few people I knew who practiced the forms truly without ego, without elevating his status or lowering that of others. He seemed to avoid authority, and when he had it he held it like a shadow. As tanto (head of formal practice), he spoke little, letting the lineaments of the moment and the established customs of our shared culture take over. The complex and highly graded mechanism by which our daily monastic life unrolled was set: he didn’t have to do much, merely oil its joints once in a while.

Near the end of that same summer, I attended evening meditation and service when Daigan served as kokyo, the one who announces the names of chants and keeps the recitation flowing. After the long weeks of heat and hard work, not many people were in the zendo. The bell was rung, the drum was thumped, and our small group stood, waiting for what we thought came next: the announcement of the Dai-i Shin Darani. Only this time, nothing happened: we heard only silence while Daigan stood there, a slight frown on his face, frozen. We waited; the silence stretched out until it became its own kind of performance. After what seemed like an unbearably long interval, a senior resident in attendance took over from Daigan and announced the chant, and the service proceeded.

Later I heard that Daigan had undergone some kind of crisis, a hiccup in his brain. Was it some kind of existential moment, of doubt in his chosen path? Was it a throwback to his days of performing, a form of stage fright? Perhaps it was physical, and he had had a minor stroke. I never knew for sure, but I do know this: that summer evening in the zendo, nothing was announced.

And even this now seems Daigan-ish to me: in the quietest, the most subtle way possible, the drama of the moment was unfolded.

Read About

Read About

Recent Comments